![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

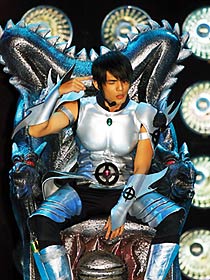

| Cool Jay |

||||

The Beatles had the Cavern Club, Elvis had Sun Studios, the Sex Pistols had the 100 Club; for Chou, this studio was his musical proving ground, where he tried out his ideas, tested theories of what made a hit, worked out how to structure a song and make it memorable and soulful and where—rare for a budding Mando- or Canto-pop star—he came to understand that it was the music that mattered, more than the looks and the moves and the image. He saw them come and go, pretty boys who could barely carry a tune, divas who had the attitude but not the talent, boy bands whose members were chosen for their dance steps instead of their voice chops. He saw that what made a performer memorable—what could make him, Jay Chou, special—were the songs themselves. And that, in the music biz as it's practiced from Taipei to Hong Kong to Singapore, was a novel idea. In the cynical, insta-pop industry of prepackaged icons that dominates greater China, it is a wonder that Jay Chou the anti-idol, now 24, exists at all. Male Canto- and Mando-pop stars are supposed to be born with connections, grow up with money and emerge in adolescence as lithe, androgynous pinups, prefabricated and machine-tooled for one-hit wonderdom and, if they're lucky, lucrative B-movie careers and shampoo commercials. How did a kid with an overbite, aquiline nose and receding chin displace the Nicholases and Andys and Jackys to become Asia's hottest pop star? The explanation starts somewhere back in that stuffy studio, with the discipline and the songs and the revolutionary idea that the music actually matters. "Even when my female fans approach me, they don't tell me that I'm handsome," Chou explains. "They tell me they like my music. It's my music that has charmed them." Since the release of his debut album, Jay, in November 2000—10 brooding, soulful, surprisingly sensual ballads and quiet pop tunes delivered with a poise that would make Craig David stand up and take notice—Jay Chou's music has ruled, and may be transforming, the Asian pop universe. Although he sings and raps only in Mandarin, Chou's CDs routinely go double or triple platinum, not only in his native Taiwan but also in mainland China, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore. Recently he was voted Favorite Artist Taiwan at MTV's Asian Music Awards, adding to a haul of more than 30 entertainment-industry honors he has won in the past two years. The Hong Kong media has anointed him a "small, heavenly King" (though Chou insists he hates the title). He recently played the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas to an audience of more than 10,000. Major companies have come calling for his endorsement, from Pepsi in China to pccw in Hong Kong. Panasonic has even stamped his profile on one of its cellular phone models—a high compliment in mobile-mad Asia even greater than being known as diminutive celestial royalty. As a boy, Chou was called retarded. Stupid. Yu tsun. Ellen Hsu, his high school English teacher, figured Chou had a learning disability: "He had very few facial expressions; I thought he was dumb." The kid couldn't focus on math, science, didn't bother with his English homework. But his mother, Yeh Hui-mei, noticed that the quiet, shy boy seemed to practically vibrate when he heard the Western pop music she used to play. "He was sensitive to music before he could walk," she recalls. Yeh enrolled him in piano school when he was four. And the kid could play. He practiced like a fiend, focusing on the keys the way other children his age focused on a scoop of ice cream. By the time he was a teen, he had developed a knack for improvisation way beyond his years. "One time he sat down and started playing the Taiwanese national anthem," says his high school piano teacher Charles Chen. "It's usually very solemn but Chou was riffing and turned it into an interesting piece of music, one that sounded like a pop song." |

![]()

©Copyright Museslave.com All rights reserved.

Unauthorized duplication in part or whole strictly prohibited by

international copyright law.

![]()